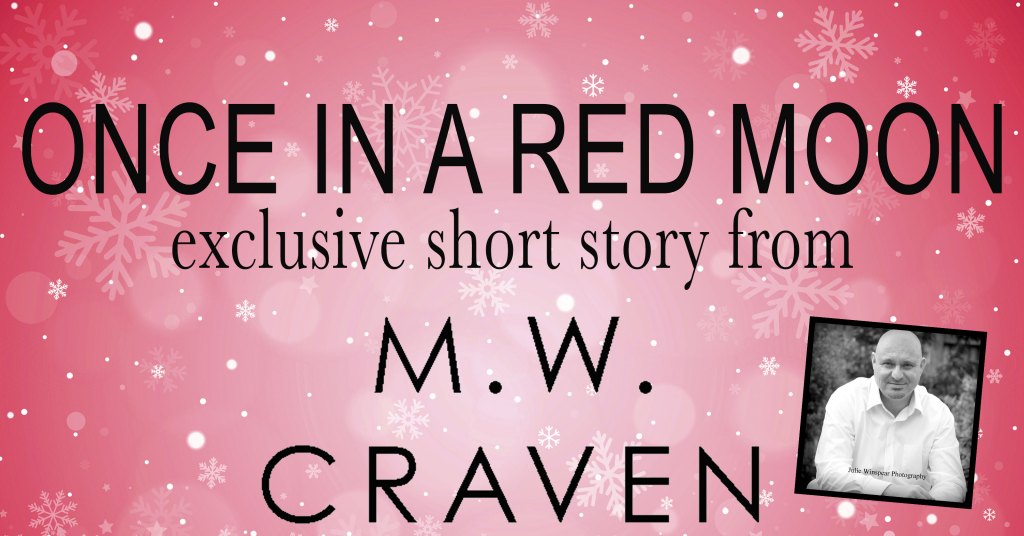

Once in a Red Moon short story by M.W. Craven

Want more of Poe and Bradshaw?

M.W. Craven has written an *exclusive* Washington Poe short story, and we are delighted to share it here with you. Enjoy . . .

‘Once in a Red Moon’

Detective Sergeant Washington Poe stared through the taxi window at the star-coated universe. The great vastness, stretch- ing into infinity, even back in time, usually grounded him. Reminded him he was a speck of nothing, and, more importantly, that anyone who annoyed him was also a speck of nothing. It put him in his place.

But not tonight. Tonight it was just irritating. Everything was.

‘Poe! Poe!’ Matilda ‘Tilly’ Bradshaw said. ‘Stop looking at the boring stars – we’re nearly there!’

‘I wasn’t looking at the stars, Tilly,’ he replied. ‘I was wondering why there’s another full moon. We’ve already had one this month.’

‘That’s because it’s a blue moon, Poe.’

‘You need a new pair of glasses. That moon’s white, not blue.

It’s not even blue-ish.’

She sighed. It was a sound he knew well. ‘A blue moon isn’t blue, Poe.’

‘It isn’t?’

‘No. It’s just the placeholder name for the occasional extra full moon. There are two definitions of what a blue moon is, but I like the second one best as it involves an astronomer called James Hugh Pruett miscalculating the length of a lunar month in 1946, proving once and for all that all astronomers are dunces and they shouldn’t even be allowed to call themselves scientists.’

Bradshaw had straightforward views on who was, and who wasn’t, a scientist. If you studied pure mathematics, you were; if you didn’t, you weren’t.

‘Remind me again why I’m here, Tilly,’ he said for at least the fifth time that day.

‘Because you agreed, Poe.’ ‘When?’

He had asked this at least five times as well. He was hoping a loophole would present itself.

‘It was after you’d shouted at your butcher for selling mince pies in September. I said we should do something when it is Christmas, and you said, “Sounds like a plan, Tilly.” That’s why I booked it.’

‘It’s possible I was distracted.’

‘I was surprised when you agreed, Poe,’ Bradshaw said. ‘I didn’t think this would be your cup of tea at all. My other suggestion was going to be a brewery tour.’

He really wished she hadn’t told him that. A brewery tour . . . or this.

‘You see,’ the driver said, interrupting Poe’s loophole fantasies, ‘what I love about driving a taxi is the freedom it gives me. Don’t want to work one day, I don’t have to. The Toon’s playing at home and I have a ticket, I’m bloody well going. It might not be the most glamorous job in the world, but at least I don’t have anyone telling me what to do.’

‘Turn left here,’ Poe said.

De Nevill Hall, ancestral home of the De Nevill family. Landowners. Farmers. Country-pursuit enthusiasts. They had made their money mining coal and copper and, until recently, it was said you could walk the Coast to Coast without leaving their lands.

That was then.

This was now.

Now they were reduced to this . . . humiliation. Poe wondered what had happened.

The tree-lined road ended in a large circle in front of De Nevill Hall itself. An ornate fountain in the middle was performing a roundabout function tonight. Cars lined up in a clockwise direc- tion, waiting to deposit their guests. As one left the space at the front of the steps, the next in line took its place and spewed out another carload.

When it was their turn, the taxi driver parked and popped the boot. By the time Poe and Bradshaw had got out, their bags were on the ground. Poe grabbed his and took in a deep breath. The air was crisp and cool and he felt it in his lungs.

He stared at De Nevill Hall. Old money stared back.

It might have been the jewel in the once vast estate, but to Poe it looked more like a Hammer House of Horror film set than one of the most important stately homes in the country. He had read up on it on the way there. It was an impressive example of English Baroque architecture, whatever that meant. It had an east wing, a west wing and more windows than he could count.

Bats flitted around the roof’s central dome, backlit by the blue moon. Poe liked bats. Not everyone did these days. Not after an undercooked one had changed the world. Poe had a family of common pipistrelles living in the eaves of his two hundred- year-old shepherd’s croft on Shap Fell. He’d sit outside at dusk and watch them catch insects, their fast, jerky flights seemingly ignoring the laws of physics.

An imposing portico covered De Nevill Hall’s main entrance.

A tall man wearing a black suit greeted them.

‘Welcome,’ he said, handing them a nametag each to fill in. ‘My name is Jim Child and I’m your host. Are you looking forward to tonight’s murder mystery evening, sir?’

‘No I’m bloody not,’ Poe said.

The oak floor was bathed in flickering candlelight. Grand oil paintings and heraldic crests jostled for space on wood-panelled walls. Except, Poe could see the occasional gap. Some had been recently removed. He wondered if they’d been sold to keep the house going. If the estate had money troubles it might explain why they were running these humiliating events.

Tonight’s play was being performed by a troupe of impro- vised comedy actors from Newcastle. They would mingle with the guests during dinner and drip-feed clues and red herrings for later. Some of their dialogue was scripted; the rest would be improvised. According to the pamphlet Bradshaw had given him, it created a more immersive experience. At the end of the meal, one of the actors would be found dead and the guests would be asked to solve the murder.

Bradshaw had said it sounded like fun.

Poe had said it sounded like something people from London did.

At least there was alcohol, he thought. Jim Child, the official greeter, was circulating with a tray of drinks. Poe grabbed a fruit juice for Bradshaw and a bottle of IPA for himself.

As he sipped his beer, he surveyed his fellow guests. Some were like him, reluctant ‘fun’-goers, dragged there by enthusiastic friends or partners, while others looked right up for it. The actors were easy enough to spot. They were out-and-out extroverts, moving from one group to the next, big grins on their faces. Poe made a note to avoid sitting next to anyone who looked happy at dinner.

One of the actors, a short woman with pink lipstick and even pinker hair, made her way to where he and Bradshaw were standing. Poe winced. Improvised comedy was the emperor’s new clothes of entertainment: it was neither funny nor interesting.

Absorbing to those involved, deadly boring to everyone else. He hoped he wasn’t about to get dragged into art for art’s sake.

Maybe it was the look Poe gave her, or maybe it was simply a matter of good luck, but all she said was, ‘Dinner is served’. She bent and read their nametags, ‘Washington and Tilly’.

There was nothing like a plate of healthy food to clear the system. And this was nothing like a plate of healthy food. They had been led into a stateroom groaning with silver, and served goose. Poe had assumed it would be turkey. He hated turkey. Suspected most people did. It was a second-rate bird, only eaten because it was big enough to feed a busload of idiots who didn’t know any better. Yes, it looked all nice and tempting when it came out of the oven, but the moment you put that dry, stringy meat into your mouth you knew you’d been taken in for the fortieth year in a row.

Goose was an entirely different matter. Dark, succulent meat glistening with warm grease. A distinctive rich flavour. Gamey, but not too gamey.

Poe’s plate was stacked high with meat, pigs in blankets, stuffing, and roast potatoes cooked in duck fat. Bradshaw had said he had to have some vegetables too. He’d added some cauli- flower cheese and she’d scowled at him.

Poe was wiping his plate with a piece of white bread when a woman ran into the room.

‘What is it, Helen?’ Jim Child said in a stage whisper. ‘It’s Rory Green,’ she gasped. ‘I think he’s dead!’

As one, the actors seated among the dinner guests rose. ‘Oh no!’ one of them cried. ‘Where?’

‘In the drawing room.’

‘Here we bloody go,’ Poe grumbled.

‘This is going to be excellent!’ Bradshaw said.

Poe recognised Rory Green from the drinks reception. He’d been one of the actors carrying drinks trays. He was a tall, gangly man. If he said his hair was strawberry blond he’d have been lying. It was ginger. He was lying on his stomach, stretched out in the crucifix position. A knife was sticking out of his back.

Even if he hadn’t been at a murder mystery evening, Poe wouldn’t have been taken in by it. The blood smelled like tomato ketchup and the knife was obviously made of rubber.

‘What do you think happened, Poe?’ Bradshaw said excitedly. ‘How the fu . . . heck am I supposed to know?’

‘Have a look then!’

Poe sighed, but kneeled by Rory Green’s prostrate body. He jammed his finger into his carotid vein. Hard. His pulse was strong and steady. Poe looked at the knife. If it had been a real stabbing, the blade would have entered the body between the two floating ribs in his back, the ribs that protected the liver. Maybe not fatal if he got to surgery within the hour.

‘OK,’ Poe said. ‘Here’s what I think happened. Someone has squirted tomato ketchup all over this man.’ He stuck his finger in the ‘blood’ and licked it. ‘Heinz, if I’m not mistaken.’

Bradshaw glared at him.

‘Did anyone bring fish fingers?’ he added. ‘Take it seriously, Poe!’

‘OK,’ Jim Child said. ‘We have a body in the drawing room and no one is leaving until we’ve found the murderer.’

‘Shouldn’t we call the police?’ Poe said. ‘Assisting an offender is a serious offence. We could all get ten years. I think we should call the police.’

Child ignored him.

‘Helen tells me the last people to see Rory were her, Peter, Derek, Margot and Sharon. They’re currently sequestered. The rest of you should have a chat and decide how you want to do this. I suggest you nominate someone to lead and take it from there.’ ‘I have a decent batting average with these things,’ a man with bulging eyes said the moment Child had left the room. His name badge had Giles written on it. ‘Here’s what I want everyone to—’

‘Poe should be in charge!’ Bradshaw cut in. ‘Tilly, I don’t think that’s such a good idea—’

‘Don’t be such a Mr Cranky Pants, Poe.’ She turned to the rest of the guests and said, ‘Poe’s a detective sergeant with the Serious Crime Analysis Section and he’s caught loads of serial killers. He even solved the murder in the Michelin-starred restaurant and people said that was almost the crime of the century! I bet he could easily solve this one.’

‘He’s a policeman?’ Giles sneered. ‘My word, this place really has gone to the dogs.’

A horse-faced woman standing next to him tittered. The rest of the guests had the grace to look embarrassed.

Poe turned to Bradshaw.

‘I thought you said there wouldn’t be people like him here?’ ‘People like who, Poe?’

‘The result of cousins being allowed to marry.’

‘I didn’t think there would be,’ she said. ‘Cross my heart and hope to die.’

‘I feel you’re being rude, sir!’ Giles snapped.

‘I am being rude,’ Poe said. ‘That’s why you can feel it. But, please, feel free to teach me a lesson.’

Giles skulked off and began muttering to Horse-Face.

‘This is a bit of a busman’s holiday for you, what!’ a ruddy- faced man wearing a cummerbund said. ‘What do you say, Washington? The sooner we solve this, the sooner we get our dessert. I understand it’s treacle tart tonight. Real custard.’

‘Why wasn’t this mentioned before?’ Poe said. ‘Tilly, fetch me my interrogation truncheon.’

‘You don’t have an interrogation truncheon, Poe,’ she said.

‘And even if you did, using it would be an egregious breach of the 1967 Criminal Law Act as it pertains to the use of reasonable and proportionate force.’

‘Shame. Would have made this go so much quicker.’ ‘Are you not enjoying yourself, Poe?’

He looked at Giles and Horse-Face. They were still muttering together. Poe recognised a pair of plotters when he saw them.

‘Not really, Tilly,’ he said. Her face fell.

‘But I’ll give it a go,’ he added.

He looked at the corpse. It shut its eyes.

‘OK, if I were the senior investigating officer at a fresh crime scene, I’d usually ask for a forensic pathologist to attend. Make sure things like rectal swabs were taken.’

‘Steady on,’ the corpse said.

‘But, in the circumstances, I suppose we can jump ahead and get the witnesses in. See what they have to say for them . . .’ He looked off into the distance.

‘What’s wrong, old chap?’ Cummerbund said.

Poe walked to the door and pointed at a small oval-shaped mark. It was about three-and-a-half feet off the floor and had clearly just been placed. He smiled. He returned to the group. ‘Tilly, can you lie down next to Mr Green please?’

‘I can, Poe.’ She did.

‘You’re a bit too short,’ he said. He scanned the rest of the guests. He pointed at Giles. ‘You look the right size. Lie down next to him.’

‘I’ll do no such thing!’ he snarled. ‘Have you any idea how much this suit cost?’

‘You bought it?’ Poe said. ‘I assumed you’d borrowed it from a ventriloquist’s dummy.’

‘Damn you, man!’

Poe sighed. ‘OK, if you won’t join in, just tell me how tall you are.’

Giles’s cheeks quivered, and for a moment Poe thought he was going to refuse. ‘I’m six feet,’ he said eventually.

‘My arse you are. How tall are you really?’ ‘Five ten,’ Giles admitted.

‘This is a bit unconventional,’ Poe said, ‘but can I ask the deceased how tall he is?’

The corpse said nothing.

‘It’s either that or we’re back to the rectal swabs,’ Poe added. ‘I’m five foot ten,’ it said.

‘Excellent.’ Poe pointed at the door and told Giles to stand next to the mark.

‘Waste of time,’ Giles muttered. He did as he was asked, though.

Probably wanted Poe to get it wrong so he could take charge. ‘Can you stand so we can see your back and the mark at the

same time?’ Poe said.

Giles moved a foot to his left and turned sideways on.

Poe pointed at the mark on the door. ‘See how it’s the same height as Giles’s liver. As they’re both five ten, it means the mark is the same height as the victim’s liver.’

‘What are you saying, old chap?’ Cummerbund said.

‘Rory Green wasn’t murdered, he committed suicide,’ Poe said. He pulled a pen out of his inside pocket, reached up behind him and held it against his back at a right angle. He then backed up to the door and, when the pressure of his back was enough to stop the pen falling to the floor, he stood still.

‘With the blade resting against his back, Rory Green held the hilt of the knife against the door,’ he explained. ‘He then thrust himself back on to it. Once the blade was in, he staggered forwards and collapsed where we found him. If we had a full forensic team we’d find blood-spatter evidence that starts at the door and leads to where he is now. Case closed.’

‘Couldn’t he have been stabbed and staggered back on to it?’ ‘No. If that were the case, the mark on the door would have been more of a scuff.’ Poe pointed at the door. ‘This is the exact shape of the knife’s hilt. Means the knife went in at a right angle, and that doesn’t happen in stabbings. Not at liver height. This wound was self-inflicted. I guarantee it.’

The silence that followed was broken by clapping. They turned. It was Rory Green. He was sitting up. ‘Six years I’ve been doing this and not once has this play been solved,’ he said.

‘I told you,’ Bradshaw said. ‘Poe’s a brilliant detective.’

Jim Child entered the drawing room. ‘Don’t go patting your- selves on the back just yet,’ he said. ‘Rory was obviously trying to set someone up for murder. You still need to interview the wit- nesses and find out why.’

‘Yay,’ Bradshaw said.

‘Can you take over, Tilly?’ Poe said. ‘I need to write up my report.’

‘Really?’

‘Of course not. I’ve had enough. I’m going to find this treacle tart I’ve been promised.’

As it happened, Poe didn’t find his pudding.

Not yet.

But he did find the library.

An old man was hunched in an armchair, sipping an amber drink. With his free hand he thrust an ornate poker into the roar- ing log fire. His hair was grey-white and thinning, and his scalp was blotchy. Poe put him in his seventies.

He noticed Poe in the doorway. ‘Not enjoying yourself?’ he said.

Poe shrugged. ‘My friend Tilly dragged me here,’ he said. ‘Not really my thing. Are you one of the guests? I didn’t see you at dinner.’

He waved his arms. ‘I’m Sholto De Nevill,’ he said. ‘I’m Poe.’

They shook hands.

‘You’re the owner?’ Poe said. ‘I prefer “custodian”, but yes.’ ‘You have a beautiful home.’ ‘It’ll be a hotel soon.’

Poe nodded, unsurprised. The missing paintings, evenings like this, it all pointed to financial problems. De Nevill was asset stripping and diversifying, like any good business would, but sometimes you were beaten by circumstances. ‘You have money troubles?’

De Nevill raised his not inconsiderable eyebrows.

‘I’m a detective,’ Poe said. ‘Which is another name for a professional nosey bastard.’

De Nevill laughed. ‘Will you take a whisky?’

‘Thank you,’ Poe said, lowering himself into the armchair opposite.

De Nevill poured him a generous measure from a long- necked, cut-glass decanter.

‘What happened?’ Poe said. ‘I doubt I’m the only one who dislikes evenings like this.’

‘We have debts to service,’ De Nevill said. ‘But you’re right, of course, I’m too old for strangers to have free run of the house. We did one of these things last Christmas and some idiot unscrewed all the baubles on the tree.’

‘That’s peculiar vandalism,’ Poe said. ‘They mess with anything else?’

‘Just the baubles.’ ‘Expensive?’

‘No. Cheap things Lady De Nevill bought in bulk to decorate all the trees on the estate. They were hollow, so she could fill them with treats for the children. It’s a family tradition to buy the staff their trees and decorations. Put some presents under them.’

‘Strange enough to spook you, though?’

‘Lady De Nevill won’t come downstairs now when these events are on.’

Poe sipped his whisky. It was good. Burned his throat and warmed his stomach. ‘There’s no other way to find what you owe?’

‘I’m afraid we’ve rather exceeded our line of credit.’

‘Was it the economy? I’ve heard these big houses are expensive to run.’

De Nevill swirled his whisky before draining it. ‘Did you know tonight is a blue moon?’

‘I did, as it happens,’ Poe said.

‘Well, the fall of the house of De Nevill wasn’t caused by a blue moon,’ he said. ‘But it was caused by a red moon.’

Poe put down his glass. ‘Tell me what happened,’ he said.

‘Have you heard of the Red Moon of Coonowrin, Washington?’ De Nevill said.

‘I haven’t.’

‘It’s a five-carat, brilliant cut, unmounted red diamond. Incredibly rare, extremely valuable. It was found two hundred years ago in a riverbed near Mount Coonowrin.’

‘Which is where?’

‘An Aboriginal mountain in Queensland.’ ‘And your family owned the diamond?’

‘Goodness, no,’ De Nevill said. ‘But we did lose it.’

‘The Red Moon of Coonowrin belonged to a private collector from Sydney. Man called Simon Cowdroy. He’s a bit of a dilettante, and for years had been able to tour the world’s great houses simply by bringing his diamond with him. He would claim it was to see their private art collections, but really he wanted to be wined and dined and fussed over.’

‘And you hosted him?’

‘Almost two years ago to the day,’ De Nevill said. ‘It was a bit of a coup, actually. He’d been touring Europe and London, but had wanted to shoot some grouse before the season ended on the tenth of December. There’s only us and the Doyles who keep grouse moors up here and I got the nod. Put him up for the night and let him carry a gun the following day. Seemed a small price to pay.’

‘Seemed?’

‘As Cowdroy’s itinerary was not advertised, the security of the diamond was deliberately low key. The house was expected to have insurance and to provide someone to watch over it the entire time it was there, but otherwise there was just a private security guard and a briefcase with a chain.’

‘Let me guess,’ Poe said. ‘As the house was full of supposedly honourable men and women, the diamond was kept on display most of the time.’

‘It was,’ De Nevill nodded. ‘In this very room, as it happens. I’d asked my estate manager, a man called Lytollis, to watch over it. Lytollis had been with the family for twenty years and I believed he was entirely trustworthy. And, as he was ex-Cold- stream Guards, I thought if anything were to happen, Lytollis wouldn’t be found wanting. Other than my guests, his wife was the only other person in the house that night. She was helping to serve supper.’

De Nevill refilled their drinks. He opened a carved wooden box on the table. ‘Cigar? They’re Cuban.’

Poe checked Bradshaw hadn’t suddenly sneaked in – he could do without another PowerPoint presentation on tongue tumours – before saying yes. De Nevill selected one and cut it. He then warmed the end, lit it and passed it over. He took one for himself and settled back into his story.

‘My oldest and dearest friend was with us that night. A great man called Charles Buxton. He was a Chichester fellow, but we’d known each other since Eton. He’d never missed one of my driven grouse shoots and I’d never missed one of his.’

‘Was a Chichester fellow?’

‘He died that night. In this room. Massive heart attack.’ ‘The same room as the diamond?’

‘Indeed.’

‘Who else was there at the time?’ ‘Just Lytollis.’

‘No one else?’

De Nevill shook his head. ‘Lytollis left the room to raise the alarm, but the room was filled with concerned guests within seconds. Cowdroy and I had been having a drink on the terrace, but we were there within a minute too.’

‘And you noticed the diamond was missing?’ Poe said. ‘I did.’

‘There was a police investigation?’ ‘And one by the insurance company.’

‘Do you have a note of the sequence of events I could look at?’ Poe said.

‘I do,’ De Nevill said, ‘but I know it word for word. Ask me your questions.’

‘Lytollis and Charles Buxton were alone with the diamond. Your friend suffers a heart attack and presumably collapses. Lytollis runs out to raise the alarm.’

De Nevill nodded. ‘Who was first in?’ ‘Charles’s son, Giles.’

‘Not that bug-eyed bastard who’s been annoying me all evening?’

‘He is a bit of an acquired taste.’ ‘He’s a prat.’

De Nevill tipped his head in agreement. ‘It’s true he’s no Charles. But he does what he can to help. Always attends these events even though he doesn’t like them any more than you do.’

‘How long was Giles alone in the room?’ ‘No more than twenty seconds.’

‘He was searched by the police?’

‘We all were. And Giles never left his father’s side. He certainly didn’t leave the room.’

‘The house was searched?’

‘Thoroughly,’ De Nevill said. ‘It was as if it had vanished.’

Poe took a drink. Swirled the whisky around his mouth. ‘I assume the police think Lytollis stole it?’ he said. ‘Used the distraction of Charles’s heart attack?’

‘They believe he slipped the diamond into his pocket and, after raising the alarm, passed it to his wife. She spirited it out of the house before anyone noticed it was missing.’

‘He was interviewed?’

‘He was. Denied it, of course.’ ‘And his wife?’

‘The same.’ ‘Charged?’

De Nevill shook his head. ‘All the police had was what they called circumstantial evidence. We were told the Crown Prosecution Service couldn’t prosecute.’

‘The insurance investigation?’ ‘The same conclusion.’

‘But they denied your claim?’

‘Indeed. Said that, as Lytollis was my man, they couldn’t rule out collusion. I threatened to take them to court but they counter- threatened with insurance fraud.’

‘You had to compensate Cowdroy yourself?’

‘Which came to more than we had. Wiped out our reserves, and even after we’d sold some of our major assets we were still short. Cowdroy was a good sport, though. Didn’t blame me. His solicitors worked out a repayment package. I’ve been trying to stave off the inevitable with events like this, but in two months I will run out of options and have no choice but to sell the only asset we have left: De Nevill Hall itself. A consortium has been pestering me for an answer on their bid to turn it into a hotel.’

They settled into an unhappy silence. Poe tried to imagine De Nevill Hall as a country hotel. Decided he didn’t like the idea. He’d known Sholto less than half an hour but knew he would never recover from this.

Poe knew a bit about moving high-value items; the National Crime Agency had a unit dedicated to it and he read their brief- ings when he had nothing better to do. He knew that, even with the right connections, moving a gem such as the Red Moon of Coonowrin would be problematic. It was unique, easily identi- fiable and people were looking for it. A crooked private collector might buy the diamond, but he would never be able to show it. Organised crime bosses occasionally bought things like this to use as collateral in case of an arrest, so it was possible the diamond was in a vault somewhere, waiting for the right time to be used.

But Poe didn’t think an ex-guardsman such as Lytollis would have had the first clue about moving a large diamond. He’d have been caught the moment he tried. And De Nevill didn’t seem daft – how had he judged Lytollis’s character so badly?

‘Have you spoken to him recently?’ Poe said. ‘Lytollis?’

‘Yes.’

‘Not since I dismissed him.’ ‘You are sure it was him?’

‘I’ve spent a long time thinking about this,’ De Nevill said. ‘I don’t want to believe it, but logically he was the only person it could have been. And as Sherlock Holmes once said, “When you have eliminated all that is impossible, then whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”’

Which was when Poe’s brain snapped to attention.

The quote was taken from The Sign of Four, but it wasn’t the tale of treasure and treachery in India, it was a different Sherlock Holmes story Poe was thinking of. He had a theory, and, if he were right, Rory Green’s suicide might not be the only thing he solved that night.

He opened his phone and thumbed Bradshaw a text explaining what he needed her to do. ‘How familiar are you with Arthur Conan Doyle’s canon, Sholto?’ Poe said after he’d sent it.

‘I read them in school. Why do you ask?’

‘Do you remember “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons”?’

‘Why don’t you have a Christmas tree, Sholto?’ Bradshaw asked across the crowded dinner table.

Why Rory Green had killed himself, and who he’d been hoping to frame, had been solved by the guests. Apparently, it was something to do with unrequited love. They were now back in the dining room, eating the promised treacle tart. Much to Bradshaw’s disgust, Poe had already eaten three large slices.

‘We used to decorate all the trees in the estate houses, Tilly,’ De Nevill replied, putting down his coffee cup. ‘Lady De Nevill bought baubles and lights in bulk as it was cheaper that way. We reused them year on year.’

‘But not this year?’

‘No, dear. Even appearing to spend money on frivolities wouldn’t be fair. We have debts to service and our creditors must come first. As it happens, Lady D has just packed up the estate Christmas tree decorations. She’s donating them to charity. There’s a box load of the stuff in the library if you want to take some home. I’m sure she wouldn’t mind.’

‘No, thank you, Sholto,’ Bradshaw said. ‘My mum always decorates our tree, and Poe says if he wanted to find pine needles in the crack of his bottom for a month he’d go and live in a forest.’

De Nevill exploded with laughter. Poe knew part of it was nervous energy. Bradshaw had played her part well.

The trap had been baited.

Now all they could do was wait.

Someone was on the other side of the library door. Poe could hear them trying to control their breathing. Working up the courage to step inside. Wondering if their patience was finally about to pay off.

Poe tapped De Nevill on his shoulder and made sure the old man was ready.

Doing this was arguably irresponsible. They were engineering an unnecessary and unpredictable situation. The puzzle was already solved. They should have called the police. Allowed them to take the lead. Justice would be swift and certain.

But this wasn’t only about justice. This was also about reputations. Reputations restored, reputations lost.

And that had to be done publicly.

The door opened and someone slipped into the library. The lights were off and the room was pitch black. The person stood still, no doubt waiting for their eyes to adjust to the darkness.

After a minute, Poe heard them walking, slowly, testing each step as they did. Floorboards built this solidly didn’t creak, but this person was being careful. Poe didn’t blame them. It was a high-stakes game they were playing.

They made their way across the room, passing within feet of the seated, statue-like Poe.

Poe sensed rather than saw them feel for what they had come for.

They found it. They opened it.

They began searching.

‘What the hell?’ a familiar voice muttered.

Poe flicked on the standard lamp by his chair.

‘Hello, Giles,’ De Nevill said. ‘I bet you’re wondering why the box is empty.’

Giles Buxton froze but recovered quickly. ‘Ah, Sholto,’ he said. ‘I was just looking for my watch. I thought I might have dropped it here earlier.’

‘In the dark?’ De Nevill said.

‘Yes, I wondered about that. Why are you sitting in the dark, Sholto?’

‘We were waiting for you.’ ‘You’ve found my watch?’

‘How could you, Giles?’ De Nevill said. ‘Your father was my best friend.’

Giles pointed at Poe. ‘Sholto,’ he said, ‘I don’t know what this man has told you, but I can assure you I am as loyal as I ever have been.’

De Nevill didn’t respond.

‘Was it this you were looking for, Giles?’ Poe said. He showed him an evidence bag . . .

. . . that contained the Red Moon of Coonowrin.

Poe held it up to the light. ‘It’s rather pretty, isn’t it?’ he said. ‘Good Lord!’ Giles said. ‘You’ve found it! Sholto, you must

be thrilled.’

‘The missing Red Moon of Coonowrin is missing no more,’ Poe said. ‘But you knew that, didn’t you?’

Giles faced De Nevill. ‘I have no idea what’s going on here, Sholto. I hope you aren’t trying to deflect the blame on to me, though? Because, to people on the outside, it might appear that you were in on the theft from the beginning, but have only now realised you can’t sell it. If you try to blacken my name with this, money troubles will be the least of your worries.’

‘Oh, shut up,’ Poe said. ‘We both know that when the diamond is examined, it’ll be your fingerprints and your DNA they find on it, not Sholto’s. Science doesn’t lie.’

Giles lunged for the bag but Poe was too quick. He put it in his inside pocket.

‘Nice try,’ Poe said. ‘Sorry, Giles, but it’s too late to try and get your prints on it now. The evidence bag is sealed and I was videoed putting the diamond inside.’

‘Damn you to hell, man!’ Giles yelled.

Drawn to the commotion, the rest of the dinner guests began to gather in the library. Only Bradshaw knew what was happening.

‘What’s going on, Washington?’ Cummerbund said. ‘We heard raised voices.’

‘It seems it was Giles who stole the Red Moon of Coonowrin,’ Poe said. ‘Sholto and I have just caught him attempting to recover it.’

‘They did no such damn thing!’ Giles hissed. ‘You’d be well served to ignore this odious little man. He’s nothing more than a common thief-taker and my solicitors will own everything he has soon. And anyone else who utters a word about this will wish they hadn’t.’

Poe continued unperturbed. ‘You see, when his father suffered that massive heart attack two years ago, Giles was first in the room. But instead of tending to his dying father, he took advan- tage of the temporarily unguarded diamond and hid it. He didn’t have long and he knew if it were found he could say he’d been playing a prank.’

‘But where could he have hidden it?’ Cummerbund said. ‘I’ve heard the story, we all have. Everyone was searched. The room was searched. The house was searched. It wasn’t there.’

Poe reached into his jacket and removed a second evidence bag.

It contained an unscrewed Christmas bauble.

‘He hid it in this, of course,’ he said. ‘You’re quite right, the room was searched, but who would think of checking the inside of a Christmas tree decoration?’

The dinner guests turned to look at Giles. His face was beetroot red.

‘Giles thought it would be a simple case of coming back the following year and collecting it at his leisure,’ Poe continued. ‘It was why last year’s baubles had been unscrewed. And because they’d all been unscrewed, it meant he probably hadn’t found it. Because what Giles didn’t know was that the baubles had been bought in bulk, and the ones on the tree last year weren’t the same ones as the year he hid the diamond. So, when Sholto told Tilly that the baubles were boxed up in the library, ready to go to charity, Giles had no choice but to recover the diamond tonight. Unfortunately for him, Sholto and I had already been up to the attic and found it. The box in the library was actually empty. The cheese in our little rat trap.’

Giles glared at Poe, wild eyed and panting. Poe recognised a ruined man when he saw one. Knew he only had one play left. Giles had to touch the diamond and bauble somehow. Had to find a way to explain why his prints were on them. Poe readied himself.

Giles grabbed the whisky decanter. He held it by the neck and took a step towards Poe. ‘Not so cocky now, are you, you damn insolent man?’ he snarled. ‘If this were fifty years ago I’d have had you horsewhipped and be done with it. Now, pass me that bloody diamond!’

He took another step. Poe didn’t move.

‘I’m warning you, man! Hand it over!’ He raised the heavy decanter. Whisky sluiced down his sleeves but he was past caring about his expensive suit now.

‘Poe!’ De Nevill shouted, throwing him the ornate poker. Poe caught it. ‘Will you look at that, Tilly?’ he said. ‘It seems I do have an interrogation truncheon.’ He bopped Giles on the arm. The decanter fell to the floor.

‘Ow!’ Giles cried.

Poe forced him to the ground and knelt on his back. He looked up at Bradshaw. ‘Hey, Tilly?’

‘What is it, Poe?’

‘This has been fun,’ he said. ‘Can we do it again next year?’

For more Washington Poe and Tilly Bradshaw adventures you can buy M.W. Craven’s latest book Dead Ground online or in your local Tesco and Sainsburys

Winner of the prestigious CWA IAN FLEMING STEEL DAGGER AWARD 2022

Longlisted for the Theakston Old Peculiar Crime Novel of the Year 2022

'Heart-pounding, hilarious, sharp and shocking, Dead Ground is further proof that M.W. Craven never disappoints. Miss this series at your peril.' Chris Whitaker

'Dark and entertaining, this is top rank crime fiction.' Vaseem Khan, Author of the Malabar House series and the Baby Ganesh Agency series

'M. W. Craven is one of the best crime writers working today. Dead Ground is a cracking puzzle, beautifully written, with characters you'll be behind every step of the way. It's his best yet.' Stuart Turton

'Fantastic' Martina Cole

'Dark, sharp and compelling' Peter James

'You can taste the authenticity' Daily Mail

Detective Sergeant Washington Poe is in court, fighting eviction from his beloved and isolated croft, when he is summoned to a backstreet brothel in Carlisle where a man has been beaten to death with a baseball bat. Poe is confused - he hunts serial killers and this appears to be a straightforward murder-by-pimp - but his attendance was requested personally, by the kind of people who prefer to remain in the shadows.

As Poe and the socially awkward programmer Tilly Bradshaw delve deeper into the case, they are faced with seemingly unanswerable questions: despite being heavily vetted for a high-profile job, why does nothing in the victim's background check out? Why was a small ornament left at the murder scene - and why did someone on the investigation team steal it? And what is the connection to a flawlessly executed bank heist three years earlier, a heist where nothing was taken . . .

Praise for Dead Ground:

'Unmissable' Sunday Express

'I've been following M.W. Craven's Poe/Tilly series from the very beginning, and it just gets better and better. Dead Ground is a fast-paced crime novel with as many twists and turns as a country lane. I can't wait for the next one.' Peter Robinson

'Dead Ground is both entertaining and engaging with great characters and storyline. I loved this first dip into the world of Tilly and Poe!' BA Paris

Praise for M W Craven:

'A brutal and thrilling page turner' Natasha Harding, The Sun

'A thrilling curtain raiser for what looks set to be a great new series' Mick Herron

'One of the most engaging teams in crime fiction' Daily Mail

'A powerful thriller from an explosive new talent. Tightly plotted, and not for the faint hearted!'

David Mark

'A gripping start to a much anticipated new series' Vaseem Khan

'Satisfyingly twisty and clever and the flashes of humour work well to offer the reader respite from the thrill of the read.' Michael J. Malone

'Nothing you've ever read will prepare you for the utterly unique Washington Poe' Keith Nixon

'Beware if you pick up a book by M.W. Craven. Your life will no longer belong to you. He will hold you spellbound.' Linda's Book Bag

'Craven's understanding of the criminal world is obvious in this cracking read' Woman's Weekly

'Breath-taking' Random Things Through My Letterbox

'5 Stars... another fantastic literary experience and a welcome addition to the already brilliant Poe and Tilly series' Female First

'An explosive plot, slippery twists and my fave new crime-busting duo...Fantastic!' Peterborough Telegraph