Aspects of the Devil – Exclusive from Craig Russell

ASPECTS OF THE DEVIL

by Craig Russell

Hrad Orlů. Central Bohemia. April 1931.

The castle and the village that huddled in the deep, narrow valley beneath it seemed bound, one to the other, as if conjoined in a shared dark fate: united by some single, indissoluble, yet unspoken destiny.

As Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Ondřej Románek stood at the window of the ancient castle room, he knew that his presence in this place, and the new function he had for it, was severing that bond. He also knew he and the other state officials had earned the resentment of the locals for it. Turning from the stone-framed view of the village far below, he directed his attention once more to the castle room, newly fitted out as his office, and his task of unpacking the crates of books and files. From one he took a photograph of a handsome yet sad-looking woman and put it on his desk—a vast, grand piece of carved Hungarian oak—that he’d had shipped from his previous posting. It was a small act, but the placing on the desk of the image of his ten-year deceased wife seemed a gesture of permanence, of finality. This was his place now, and the dark task ahead was also his. The castle-turned-asylum was within days of being ready to receive its patients.

Only six would be confined here. Six madnesses so dark and deep and feared that only this remote, impenetrable castle had been judged secure enough and isolated enough to confine them. And only Ondřej Románek had been judged skilled enough as a psychiatrist to manage their confinement.

They would be here in a matter of days.

It was a prospect that inspired the strangest mix of feelings in Románek. As a psychiatrist, it thrilled him; as a man, it frightened him.

And then there was the castle itself: Hrad Orlů had centuries long stood in imperious dark vigil over the village, over the shadowed ravines and dense forests that surrounded it. The erstwhile hunting castle of the notorious Jan of the Black Heart was now Hrad Orlů Asylum for the Criminally Insane. That fact had been enough in itself to provoke the hostility of the local population, but then the rumour – founded in truth – had started: that the converted castle was to become home to the infamous Devil’s Six. The most notorious and dangerous homicidal lunatics in Central Europe.

During the months of preparing the castle for its new function, Románek had spoken to few of the villagers, other than the handlebar-moustachioed landlord of the local inn, who affected a professional friendliness whenever he served the professor. The other villagers he had encountered had said nothing to him, but their gazes had spoken with great eloquence of their hostility and mistrust. But it wasn’t that the locals held the castle in some particular affection. The professor, whose business it was to understand the workings of the human mind, soon came to realize that the villagers were not expressing proprietorial feelings toward the castle, but a real, deep-seated fear that any disturbance of its fabric would awaken dark and unfathomable forces.

Románek knew the legend, of course. Long, dark centuries before, Hrad Orlů had been part built, part hewn out of the dense rock of the mountain, not to offer any strategic or infrastructural value, but simply to stop up what had been believed to be the Mouth of Hell. The mountain on which the castle was built was riddled with a network of caves and tunnels that spiralled down into the very maw of hell. It was said that before the castle’s construction, the skies around the mountain would teem with reeling shadows of winged demons, and the bald rock and dense forest had been infested with all manner of infernal beasts and monsters.

Hrad Orlů had been built, first and foremost, to seal this gateway between realms. And ever since that time, it was said, the castle was destined to draw all forms of evil to it.

The most notorious of all those evils had been that of the mediaeval aristocrat Jan Černé Srdce—Jan of the Black Heart—who had chosen the remote castle as his hunting lodge and, distant from the view of the Emperor’s court, had become absolute ruler of his sequestered dominion. Legend had it that Jan of the Black Heart had sold his soul to the Devil –but it was a fact of history that he had rejoiced in acts so unspeakable and barbaric that he had eventually been condemned to be walled up in the tower of his own castle. Local folklore asserted that Jan of the Black Heart had a secret network of tunnels that allowed him—first in body and now in spirit—to escape at will his immured confinement and continue to slake his bloodlust at will.

Like the castle that had been his home and had become his prison, Jan of the Black Heart still cast a dark shadow over the village. When, nearly a year before, the conversion of the castle had begun, none of the local men had been willing to take up the offer of well-paid work, and it soon became clear that no villager could be coaxed to come near the castle.

For a man of reason and science such as Románek, with his mission to cast light into the darkest minds, it was all but inconceivable that people in the twentieth century should still adhere to such superstition. There again, these were people who knew little of the outside world, descended from countless generations who had never dared venture beyond the horizon.

Because of the reluctance of the locals to engage in any way with Hrad Orlů, contractors and labourers had been brought in from Mladá Boleslav—even as far as Prague—to complete the conversion and restoration work. Románek found himself losing patience even with these urban types who, lodged locally, seemed to have become infected with superstitions. There had been several incidences of workmen, going about their trade in some isolated castle room, suddenly calling out in terror at some imagined spook lurking in a corner. Hysteria, as Románek knew only too well, was infectious and he had urged the clerk of works, a heavy-set, saturnine Silesian called Procházka, to move his men out of the village and into a worksite camp, focus them on the task at hand and keep the conversion of the castle on schedule.

Now, as the conversion work was all but complete, the winter was beginning to yield the sky to brighter promises, yet the louring castle, the hunchback rock massif on which it sat and the dark forest that cloaked it all seemed immune to spring’s blandishments.

The foreman Procházka suddenly burst into Románek’s office.

“One of the men has been injured,” he said urgently.

“How?”

“It’s Holub, one of the masonry men – he was working in one of the rooms we’re converting into confinement cells. The idiot somehow managed to pull a loose stone from the wall onto himself. Can you come and see to him?”

Románek nodded. The other staff, including Dr Platner, who would be in charge of general medicine, had not yet taken up their appointments. Until they did, Románek was the only medically qualified person on site.

When he and Procházka arrived in the room the hurt man, Holub, was being attended by two of his workmates. The cause of his injuries lay darkly on the floor inside the cell: a half-metre-wide stone, its surface black and smooth, its origin marked by the black tooth-socket gap high up on the wall. The air in the room fumed with the overpowering smell of petrol exhaust and the professor could see where a generator rumbled in one corner. The lamp it powered still shone but lay toppled onto its side.

“Switch that thing off!” commanded Románek. “What the hell was he doing with that in here?”

“The power’s been disconnected,” said Procházka, “until the magnetic locks system has been fitted to the cell doors. It won’t come on till later today and we’ve been using the petrol generators.”

Románek struggled to catch a breath. “No wonder there’s been an accident in here. The air is full of carbon monoxide. It’s a miracle he wasn’t overpowered. Get him out into the hall so I can examine him.”

Procházka swiched off the generator and the two other men carried their injured workmate, who cried out in pain, into the hall. Románek followed and bent down to examine him. Holub’s right arm was badly contused and possibly fractured, as were ribs on the right side of his chest.

“How on earth did this happen?” asked Románek.

Holub grabbed at the professor’s jacket with his uninjured arm, his fingers scrabbling urgently for a hold.

“There was something in there. In the wall. In the stones.”

“What?”

“A shape. Like a shadow but darker than any shadow. And huge. Huge and moving. It … it rippled through the wall and pushed out the stone onto me. It tried to kill me.”

“There was nothing there,” said Románek. “You hallucinated, that’s all – just the generator exhaust mixed with whatever nonsense you’ve been listening to from the locals. The fumes made you clumsy and you dislodged the stone and brought it down on yourself.”

“No … no, it wasn’t like that at all,” Holub spoke breathlessly, making Románek worry that his rib injuries, or his inhalation of carbon monoxide, may have been worse than he thought. “There’s something living here. Something in the walls. The others have sensed it too –”

“Nonsense,” said Románek.

After he immobilized the injured workman’s arm by strapping it to his chest, he instructed the foreman Procházka to have him stretchered out and taken to the hospital at Mladá Boleslav on the work truck.

“And get a grip on these wild tales,” he ordered Procházka. “They’re putting workers at risk.”

Procházka nodded. “I’ll do what I can, professor – but I agree with Holub… this place plays tricks on the mind.”

When he was alone, Románek went back into the room, clutching a handkerchief to his nose and mouth. Without the generator-driven lamp, the only light came from the sole window, set deep in the thick stone walls. Románek made to open it to clear the air, but remembered the cell windows had already been sealed permanently shut in preparation for their new occupants. Instead he examined the stone that had fallen and injured the workman. It was very dark and smooth edged, as if no mortar had held it in place. It was also too heavy to move and the psychiatrist wondered what force could have nudged it free. He righted the workman’s stepladder and, still clamping his handkerchief to his mouth, examined the black socket that remained high in the wall, reaching in with his free hand and feeling the depth of it. Again there was no evidence of mortar. The stone had been held in place simply by the mason’s skill in achieving a perfect fit with its neighbours. As he peered unseeing into its blackness, Románek’s fingers found an object in the void and closed around it.

At that moment, the impression of something moving in the space in the wall startled him, as if an even darker shape suddenly surged towards him out of the darkness. He moved back so abruptly that the stepladder tilted beneath him and he lost his footing, falling the short distance to the stone floor, the stepladder clattering against the flagstones. He took a moment to gather himself. The fumes, he realized, were affecting him too, shaping ghosts in his imagination.

It was as Románek struggled to his feet that he looked down at his hand and realized he was still clutching it. The object he had found in the wall.

He did not examine it properly until he was back in his office. Once he had wiped the object clean of the layer of dust it had accumulated in the void, Románek could see it was a leather folder, bound with a hide drawstring. The double-headed Hapsburg eagle was discernible on the verdigris-tinged brass clasp, as was the name LEOPOLDUS. In that instant, Románek realized that, despite its excellent state of preservation, the object in his hands had not been touched by another human for nearly three hundred years.

He paused for a moment, looking at the photograph on his desk of his ten-year deceased wife. Then, with great care, he unbound the hide drawstring. He failed to suppress a small gasp when a sheaf of paper, unyellowed and its handwriting undimmed by two and a half centuries hidden from light and air, unfolded before him.

As the sun began to sink behind the hunched shoulder of the mountain, casting the castle into deeper shadow, Professor of Clinical Psychiatry Ondřej Románek began to read …

It is the year of our Lord 1698 and I declare myself Herwyg von Sybenberger, faithful and true servant of both Jesu, our Lord in Heaven, and he who is His appointed Lord on Earth, his Imperial Majesty Leopold, Holy Roman Emperor and Keeper of the True Faith. It is my sacred duty as inquisitor and examiner, appointed in my office by no less authority than that of his Grace the Prince-Bishop of Vienna, to confront and destroy the works and disciples of the Great Opposer, Satan; to seek out the Devil in all his aspects. I write these meagre lines in an attempt to describe the Great Evil I have confronted in this most ungodly of provinces, so that others may be warned of the perils of dwelling here. What follows is my Testimony and Testament. I have sinned beyond redemption and can now only pray that the Lord have mercy on my soul.

I am in my forty-fourth year, schooled by Jesuits, trained in the law, and an advocate and judge in the service of Mother Church and Empire. As such, I was called into the service of the great and pious Heinrich Franz Boblig von Edelstadt, Advocate, Judge, Master Inquisitor and Witchfinder, whom the Lord has taken to himself but this year. I served faithfully as assistant and clerk to Judge Boblig throughout the eighteen years of inquisition and trial in the Frývaldov and Šumperk region of Northern Moravia, during which time we encountered all manner of heretic, blasphemer and witch. In dungeon and examination chamber, we used the righteous tools of the inquisitor to tear from their lips that which the will of the Devil sought to conceal. We burned, in total, some hundred witches and wept for the hundred more gone undetected.

The deviousness of the Devil guised itself in the protestations of those who believed their status protected them from the Lord’s justice. They slandered Master Boblig, accusing him of turning back the world a hundred years with his methods, and claiming he had not completed his law studies and was nought more than an opportunist who had found a way to enrich himself at the expense of the innocent. We showed, however, that the Lord’s wrath knows no boundary: with our burning of the vicar of Šumperk, Kryštof Lautner, and of the Sattler family, we proved that neither position nor wealth protects those in the service of Satan.

It was upon my return to Vienna that I was summoned to the Prince-Bishop’s consistory, where I was charged with my mission by the undersecretary of the secretary of the Prince-Bishop himself. I was told of a remote Bohemian castle and its demesne, which, along with its attendant villages and estates, had a reputation for ancient ways and malevolent superstitions, and the worship of pure Evil. Such evil, I was instructed, was known to pervade the region of Hrad Orlů, yet there had never been recorded a single examination, far less execution, of a witch in the district. This, despite Hrad Orlů – the name meaning Castle of the Eagles – being of such infamy that it was known locally as Hrad Čarodějek. Castle of the Witches.

“We have received a letter,” the undersecretary explained to me, “from the current master of Hrad Orlů, the Baron von Adlerburg. He entreats us to send an examiner and judge to root out dangerous and pernicious beliefs and practices.”

“The worship of Satan?”

‘The baron does not describe it as such.” The episcopal undersecretary opened the letter and re-examined it. “He states that many local peasants have not given up that which he describes as ‘the old ways’ and furthermore declares that there ‘is much worshipping of the ancient gods of the Slavs’. He also declares that a shrine to Veles, lord of the underworld, was recently discovered in the forest and that the worship of Černobog, the Slavic lord of darkness, and Perun, the lord of thunder remains common amongst the peasants. So not Satanism as such, more crude pagan superstition.”

“Ah but there lies the error!” I protested. “All of these so-called deities are nought but aspects of the Devil – and my life’s work has been to confront the Devil in all his aspects. This pagan idolatry is the worship of the horned one. It is sorcery, witchcraft and Satanism.”

“Then you are charged with its elimination,” said the undersecretary. “Know that the Emperor and the Prince-Bishop themselves both commend you to your mission. Both also are aware that public favour has turned against witchfinding – and that the Lord’s work in which you and Master Boblig were engaged while in Northern Moravia is viewed with distaste by many.”

“Such is the power of the Great Deceiver,” I interjected passionately. “I have been all but shunned by Church and society since my return.”

“Then know this also, Master von Sybenberger, His Majesty the Emperor is a man of great learning and wisdom, schooled by Jesuits, and shares with the Prince-Bishop a loathing of the heretic Hussite, the infidel Turk, and the heathen witch. Your ways may be falling from favour elsewhere, but such are the reports of great and true evil at work in Hrad Orlů that you are instructed—on the highest authority, mind—not to refrain from the liberal use of instrument or fire in pursuit of your commission.”

So it came to pass that I travelled to Hrad Orlů. My only companion in the first stage of my journey, the coach to Mladá Boleslav, was a doctor of physic who initially engaged me in enthusiastic conversation only to deprive me of his society once he learned of my previous work with Master Boblig, and my current mission. I was accustomed to people falling into fearful silence on this discovery, but in the case of the physician, I sensed his quiet was disdainful rather than fearful. I was alone in the second coach, from Mladá Boleslav to Hrad Orlů, which was a much rougher affair than the first, and I had time to contemplate the task before me.

The countryside through which I travelled was gentle and low-lying, comprising pleasant meadow and forest spread over the quiet rolling of the land. Yet as I neared my destination I could see from my coach window that the forest suddenly thickened, darkened, like the clustering folds of some deep emerald cloak gathered around the foot of the mountain. The mountain. Never had a feature of God’s Nature inspired such dread: it surged up suddenly and brokenly from the plain, in truth looking as if some colossal force had tried to break free from the bowels of the Earth, buckling and cracking layers of rock. From a distance, it looked for all the world as if the castle and its berg had drawn in all the darkness around, the gentleness of the surrounding countryside exaggerating the mountain’s sudden violence. The lower two-thirds of its steep flanks were mantled in a forest of deep emerald green so dark as to appear almost black from a distance. Above the forest, the jagged, bald rock of the mountain’s split summit stabbed upward. And above the rock, seeming fused into it, was the castle. Hrad Orlů thrust blackly into the sky like some diseased, broken tooth and I knew on first sight of it my mission was true.

I reached into the pocket of my coat and closed urgent fingers around the Bible I carried at all times next to my heart.

The village was unexceptional. The coachman deposited me and my bags outside the tavern. My arrival was greeted by no one: the earthen ways and square of the village were empty of souls, as were the windows of the crude houses clustered around them. This was something I had become accustomed to: the arrival of a witchfinder is greeted only by the most pious and blameless. The emptiness of my welcome suggested a place where piety lacked and blame abounded.

There were only two things of note in the village square. The first was a large pyre comprising tight-packed and tar-dipped bundles of straw and branches clustered at the foot of a wooden stake. Here, in the village square in a region that had never before known a witch-burning, it seemed the means of execution had been readied for my arrival. The second striking feature was a cherry tree that stood, uncommonly abundant with leaf and fruit, in the distant corner of the square.

The tavern keeper was a large, burly man with small, pale eyes above a vast beard. When I entered, he spoke only that which his duty demanded and gave me to the care of a serving girl, whom I took to be his daughter. She served my food and drink without once looking me in the eye and I noted that her hair was raven black, her form full, and she possessed a singular beauty. Immune as I am to such temptations, I viewed her objectively. Her form and her comely darkness was of the type favoured by the Devil and I decided that, in due course, she should be examined.

When I asked about my rooms, it was her father who answered. “His reverend the priest, Father Kryštof, will attend soon, your honour. He has arranged for you to be lodged as befits your station – in the castle as guest of the baron.”

“I see,” said I. “What think you of the castle?”

“The castle?” The taverner seemed confused. “Why, your honour, the castle is the castle, nothing more nor less. I have lived my whole life in its shadow and think no more of it than I do the forest or the mountain.”

“But surely you hold it in some dread?”

“Dread, your honour?”

“Because of its reputation for great evil. Surely you’re aware of that, man?”

“I have heard the tales, like everyone else, but heed them not. But even if there be truth to them, my faith, like all true believers, is my sword and shield. My faith is greater than anything that would oppose it.”

“That I am glad to hear. But the tales of Jan of the Black Heart – of his desecrations and crimes – does that legacy not trouble you?”

“He paid for his sins, your honour. And despite what some would claim, he was nought but a man. However, not even his blood persists here: his excellency the baron descends not from that family.”

I nodded, aware that the current occupant of the castle was not of the Black Heart’s family, which had turned to the heresy of Hussitism and had been expelled after the great war of thirty years. Since then, only good Catholic nobility could hold title and property in the lands of the Bohemian Crown.

“But you hold that Jan of the Black Heart was not a witch?” I pressed the taverner.

“That is more for your honour to decide, I have no knowledge of such matters. He was never judged as such, though. As a murderer, as a taker and spoiler of women, but never as a witch.”

“But there was talk of black masses in the tower of the castle and in the forest below it.”

The taverner shrugged. “Whether those tales are true or invention in the two hundred years since, I cannot say.”

“And what of the pyre and stake I saw in the village square? Are you preparing a witch for burning?”

“We have never burned a witch here, your honour. At least not a real witch. But we do hold to the tradition of Witches’ Night. In three days’ time we will burn a witch – but not in the manner your honour is used to. We will burn an effigy of a witch to rid the land of evil and drive out the last of winter, as is the custom.”

I nodded. I was only too aware of Witches’ Night, pálení čarodějnic, as the Bohemians called it, Walpurgisnacht as the Germans had it. All over the Czech lands and beyond, witch pyres would blaze with only straw-stuffed effigies atop them. I disapproved of the custom, though the Church tolerated it, having cast around it a cloak of respectability as a celebration of St Walpurga, who had converted Central Europe to Christianity. Yet in its origin and continued practice, I saw the foul stain of paganism and fertility rite.

Father Kryštof, who had been mentioned in the baron’s letter as trustworthy and true in faith, arrived just as I was finishing my meal. I called for some more wine for us both, but Father Kryštof declined and I waved the taverner’s daughter away. It was just as well, for the wine I’d been served had been sweet, yet heavy and strong, leaving a cupric taste in my mouth and a dullness in my thoughts and movements. The priest was a short, heavy man with fleshy jowls. He was at pains to point out to me his piety and his devotion to rooting out the witch ways of his congregation, and I could see his zeal was true. I had also learned that he was, like myself, an outsider to this region, having taken charge of the parish only two months before. The priest who had preceded him had, he confided in me, been of dubious observance.

“Can you believe, Squire von Sybenberger,” Father Kryštof said, lowering his voice so none in the tavern could hear, “that these people here have the audacity to accept the sacrament, then ask me, as their priest, to take a sheaf of hazel wands to their fields to bless fertility on their cattle in the manner of some pagan warlock.”

“Have you a note of those who so asked?”

“I have, your honour.”

“Then they shall be the first to be examined.”

The small fat priest beamed at the prospect. “Then truly we shall have burnings here?” he asked eagerly.

“It surprises me you have had none to date, if devilry pervades this place as much as has been stated.”

“Indeed it is a mystery. They do not burn witches here. They have never burned witches here. But all know of your lordship’s reputation and have prepared for your arrival. There will be burnings now and it will be no bad thing. In this place all manner of man and woman – child even – adheres to the heresies of the past.

“There is a belief here—an ancient and deeply held belief—that the old gods of the Slavs, the older gods of the Celts, live in the forest and in the rocks of the mountain. They also believe that when the castle was built to stop up the Mouth of Hell, the demons that had visited our realm were trapped – but on this side of the castle, not on their own side. It is believed that the shadows seen in the forest and in the bald rock of the mountain are darker than the darkest night because they are the shades of demons let loose from hell and denied return to their natural realm. That is why we particularly needed your lordship here.”

“Why particularly?”

“I know not if those you burned in Moravia were true witches or not.”

“You doubt my work? You say I burned the innocent?” I said, outraged.

“If I do, it is not through your or Master Boblig’s ill-doing – only because the Devil seeks to deceive, to misdirect.” He drew close, lowering his voice. “You see, I fear there may be no true witches elsewhere because they are all here. Drawn to this place like all men of evil, like all creatures of darkness.”

“You believe this?” I said incredulously.

“I believe this, your lordship.”

“Then why have no witches ever been tested and burned here?”

“Because the influence of evil is so profound, so widespread, your honour.”

“Then you shall be my clerk and assistant, just as I was clerk and assistant to Judge Boblig. Together as Law and Church, we shall rid this dread place of its witches, should we have to lay waste to the whole region with righteous fire so to do.”

“And that shall be truly God’s work,” said Father Kryštof. “But if your honour pleases, we must first attend the castle, where his excellency the baron awaits you.”

Father Kryštof had a manservant of sorts waiting outside with a pony and trap. We made our slow way up from the village toward the castle, the steepness of our ascent and the pony’s labouring increasing as we drew closer; and all the while, despite the sky remaining bright, the forest clustered darkly around us, seeming as if night were trapped in its denseness. The light, or the darkness, played tricks on my eyes and as we made our way up the narrow road, I sensed movement in the shadows between the trees, as if the darkness itself took form and motion. It made me think of what the priest had said about outcast demons trapped on this side of the stopped Mouth of Hell.

“I’m sorry, your honour,” said Father Kryštof, once we had reached a small plateau in the road. “This is as far as Jiri’s pony can climb. We must walk the rest of the way, but Jiri will carry your honour’s bags.”

I nodded, but noted that the priest’s manservant seemed scarce better able to carry the burden to the summit than his pony, both being advanced in years. I also noticed that the gravel on the small level square carried multiple circular scars as if accumulated over time from the wheels of countless wagons, coaches and carts that had also used this place to turn back on their course.

The path thence did indeed rise more steeply, and I admit catching my breath when we cleared the forest and had only the bald summit and castle ahead and above us. It was not exhaustion but the spectacle of it that robbed me of breath. The castle had filled me with unease from a distance; this close it inspired dread. The summit was split by a deep ravine, the barbican on the lesser, the castle on the greater part of the rock, the chasm between spanned by a chain and board bridge, stout enough to take the weight of a carriage. Another blasphemy, Father Kryštof explained, was the local belief that the Slavic god Perun had created the chasm with a blow of his axe.

As I took in the castle of Hrad Orlů, I once more had a sense of a great darkness gathered, shadows clustered: the robust walls, the towers that cornered them, the sharp-angled roofs and the needling spires that spiked the sky – all seemed to suck the light out of the evening and combined in black threat.

We were greeted at the barbican by a tall, thin man who introduced himself as the baron’s chamberlain, and guided us across the bridge over the precipitous chasm and into the castle main.

The Baron von Adlerburg was waiting for us in the great hall. He was a man of clear nobility: tall, lean, with fine blond hair, moustache and goatee, his eyes crystal blue and his features finely wrought.

“I am so very grateful that you have come to us,” he said. “I followed closely your work with Judge Boblig and asked for you personally for, in my opinion, none other has the experience or skill to rid us of those who worship falsely. And we must be rid of those who worship falsely.”

“I am greatly honoured, your excellency,” I said, maintaining my bow. “And I will serve you to the best of my ability.”

“I am counting upon it,” he said, and frowned a little. “You do understand that you will be with us for some time, such is the scale of your task?”

“I am your servant for as long as you need me.”

“Excellent! Come, have some wine with me and the baroness. Then you can rest in preparation for your labours. We have prepared your chamber. And tomorrow you will dine as our guest.”

The chamber to which I was shown later that evening is the chamber in which you have found my testimony. Its proportions were generous enough, its fittings luxurious, and the view from its window down over the village pleasant, yet there was something about it oppressed—making me feel as if the stone of its walls lived, like the dark muscle and sinew of the castle, ready to clench tight in a grasp upon me. Before retiring, I had spent a full hour in the company of the baron and his wife. The baroness was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen—a truly profound beauty infinitely greater and more refined than the comeliness of the tavern keeper’s daughter. The baroness possessed an uncommon grace. Yet there was something cruel in that beauty, something imperious in that grace, and her presence discomfited me. Everything about the baron and baroness spoke of great nobility and breeding, yet the wine with which I was served was the same sweet, heavy fermentage as that I had been served in the tavern. And again, though I had been invited to take only two glasses, when I retired to my accommodations, I found that my head swam.

Perhaps aided by the wine and the imaginings of the evils I had been brought to expose, my slumber was rent by violent dreaming, one nightmare tumbling and clashing into the next. When I woke from these dreams, my fingers would fumble for match and candle, yet when I lit the room, the nightmares seemed to persist in the writhing of the shadows on the room’s black stone walls. At one point I became convinced I saw a large figure hunched in the corner of the room, a jangle of dark limbs filling the space from floor to ceiling, watching me with malevolent eyes that glowed dull red like dying fire-embers. At another, I dreamed—it must have been a dream though I felt I was awake—that the taverner’s daughter stood before my bed, naked and her hair a dark tumble over shoulders pale in the moonlight, before climbing into my bed and touching skin against skin.

When the full light of dawn woke me, I felt sickened and tired, as if all sleep had been deprived me. I also found bruises and blemishes on my skin that had not been there the day before. I had had so many plans for the day, but fell instead back into fitful slumbers.

The baron, when I joined him and his wife to dine later, commented on my condition. When I told him of my disturbed night, he attributed my restlessness to the strangeness of my surroundings and the prospect of my undertaking. He explained that, unfortunately, there had been a plague in the area of the biting flies that usually prey on horses, and many locals had been bitten and felt unwell and disoriented afterwards.

“That,” he said, “would explain the injuries to your skin.”

Though I protested, the baron insisted I try some of his finest wine – a special selection he had matured for ten years in his cellar. I was disappointed to find it tasted the same as the other, supposedly inferior wines, of the tavern and the night before.

“You must recover yourself before tomorrow night,” the baron protested.

“Tomorrow night, your excellency?”

“Yes, tomorrow night is the feast of St Walpurga – pálení čarodějnic,– the burning of the witches. What better way to mark the commencement of your mission here? We will have a special feast to celebrate.”

Again, that night, I was plagued by dreams that seemed not dreamed, images of darkness and spectral demons. And again, I dreamed the taverner’s daughter came to lie with me.

Despite my exhaustion the following day, I arranged to meet with Father Kryštof. Concerned about my well-being, he suggested we walk down through the trees to where an old forest chapel, built out of dark-varnished and intricately carved wood, stood in a clearing. It had not been used for some time, he explained, being associated with the evils of Jan of the Black Heart. We sat on the porch of the church and I told him of the events of the two nights of my stay in the castle. The small, fat priest listened intently and with growing excitement.

“Don’t you see? They are bewitching you! Some witch here knows that his excellency the baron, my humble self, and you, your honour, are outsiders all; as such we are immune to the devilishness that has polluted this place. They seek to stop us. They seek to stop you.”

“You believe this is witchcraft, Father?” I asked.

“I do. And I think you need look no further for your bewitcher than she who appears to you in your dreams.”

“The taverner’s daughter?”

“She is called Vesna – even that condemns her, named for the Slavic pagan goddess of spring. I have suspected her for some time,” said Father Kryštof. “One night of a full moon, I saw her walk from the village into the woods. I followed but became confused by the moon-shadows that seem to shift between the trees and I lost her in the forest, but I estimate she was keeping some satanic tryst.”

“Then she will be examined,” I said. “For she will surely carry the Devil’s mark.”

“You will sleep again at the castle tonight,” said the priest. “If she wishes to come to your dreams again, she will have to cast a spell. I will follow her close this time and watch her, so that you may have my testimony.”

“Then we are agreed upon it. We shall meet again at the pálení čarodějnic feast tomorrow. I shall tell you of my night and you shall tell me of yours.”

Arranged around the high-stacked pyre with its naked stake, no witch-effigy yet in place, the feasting tables were set in a rough semi-circle and I was bade sit beside the baron and his wife. Other than this recognition of my station, I was shocked to see that there seemed to be no social order to the seating: peasant, yeoman and lord sat mixed together. I asked the baron why the priest, Father Kryštof, had not joined us.

“Father Kryštof is central to our undertaking here,” the baron leaned towards me, so that no other could hear. “And to your mission. He will be joining us but is delayed on a matter relating to your quest here. All shall be explained when he arrives.” He sat back in his chair.

I nodded, assured that in the baron I had a true Christian ally and defender of the true faith. My impatience to talk with Father Kryštof was founded in the events of the night before: again my dreaming had conjured up dark demons from the shadows, worse and more terrifying than ever, and Vesna, the taverner’s daughter, had appeared to me again. Our coupling had been more vivid, more violent than before. I had dreamed I was intoxicated with lust by her and had caressed her smooth skin as she lowered herself upon me. But then, at the height of our sinful passion, her smooth skin had turned coarse, wrinkled and scabrous. When I looked up at her she had transformed into a hideous, demonic hag. As I screamed in horror, I became aware of the baron’s chamberlain standing at the side of the bed, watching us.

“She is a rusalka, you see,” he explained matter-of-factly. “A succubus of immeasurable age who extends her own life by extorting the vitality from her victims. She is eating your soul, witchfinder …”

I had woken from my dreaming—if dreaming it had been—exhausted, my mouth dry and my limbs leaden. I had waited impatiently the rest of that day for the feast, and the opportunity to hear what Father Kryštof had discovered.

When it was laid before us, I found the feast to be more lavish than was decent. There were great roasted flanks of venison, several roasted pigs, great mountains of sausages and other meats, and many barrels of wine. Perhaps my lingering malaise played its part in me finding it so, but the rich odours of flesh turned my stomach. Not so of the other guests, whom I now estimated to account for the entire population of the village and surrounding farms, who fell upon the feast and wine with indecent abandon. I ate little, but in the absence of anything other to sustain me and so not to cause offense to my host, I drank the wine offered me. Again I was aware of the effect on palate and mind of the thick, sweet wine and a great feeling of unreality descended upon me.

I cast my gaze around the revellers, for that is what they had become. Every now and then, one of the young women would select a male, take him by the hand and lead him over to the single cherry tree that grew in the far corner of the square, where they would kiss under the tree’s boughs before returning to the feast. I recognized the practice: a ritual to ensure fertility in the coming spring and summer. A heathen, base rite that had no place among a Christian congregation. I complained such to the Baron, who dismissed me with a wave.

“We have worse and greater heresies to eliminate,” he said. “Your energies will be best directed on them.” He bade me drink more wine, which I did, as I seemed to be becoming accustomed to its rich and sweet flavour, and I admit my head and judgment had lightened with the wine’s potency and my lack of sleep and food.

Time became fluid, confused: the afternoon yielded to evening and the sun sank behind the mass of the castle and its mount. My head swam and I foreswore more wine, yet somehow I found my goblet continually full as I sat and watched the revelry around me. There was much dancing now, and little decency. Tallow and reed torches were lit, casting, with the last embers of the sun, shadows that reeled and swirled and twisted betwixt the reeling and swirling and twisting of the dancers.

A great dread befell me. I cast my goblet down, spilling its contents on the ground, and made to stand, but stout hands pushed me back into my chair. I turned to see two men from the village who stood behind me like guards in attendance. The baron stood up and raised his arms. A great cheer rose from the crowd.

“Brothers and sisters,” he said. “It is now time for us to put behind us cold barren winter and embrace the warm fruitfulness of the new year. It is now time for us to make our offering to Mokoš, Mother of the Earth, and Ognebog, Father of Fire.”

Horrified by this declaration, I again started to rise, but was once more restrained. The baron remained standing, his arms outstretched, while those assembled began to shriek and howl in the most inhuman way. I had, I realized, been brought into the midst of the most unholy. Two attendants raised a horned mask and lowered it ceremoniously onto the baron’s head.

“Let the burning begin! Let our offering be received!”

In that dread moment I realized why I had been summoned here. I was to burn –to perish in the flames of some heathen blasphemy. I threw myself forward to my knees and began praying, but was so overwhelmed with terror that the words failed me. I turned to the baron.

“Am I to burn, my lord? Have you brought me here simply to perish on the pyre? I beg you, spare me.”

The baron looked down at me wordlessly. Or, more correctly, the twisted, horned visage of a demon did—the mask the baron wore filled me with even greater terror and I feared I was now truly in the hands of the Devil.

“Is this revenge?” I asked the silent mask. “You summoned me here; asked for me in person. Was that to exact vengeance for the witches I burned in Moravia? Is that the true nature of this thing? I beg of you have mercy!” I am ashamed to say I remained on my knees, craven, and begged for my life. “Please, lord, spare me the flame.”

The Baron spoke from behind his mask. “We seek no vengeance here. You know well that those you burned in Frývaldov and Šumperk were not witches, merely simple Christian peasants, landholders and tradesmen you and Boblig tortured into incriminating themselves and each other – simply so that you could line your own pockets, claiming their property as payment for your tribunal. Perhaps you try to fool yourself into believing otherwise, but deep down you know that you were nothing but common thieves and murderers. All you lacked was the courage and honesty to cut the purses and throats of your victims yourselves.”

“So is that why you have brought me here? Retribution? I beg your mercy, lord. Forgive me my sins.”

“Here, sin is something we recognize not in its avoidance or punishment, but in its commission, in its celebration. This is a dark place, Master von Sybenberger, and it attracts all manner of dark souls. Dark souls such as mine. Such as yours. All you have been told since you came here has been the truth. You were informed that we have never burned a witch here – well, that is true. We do not burn witches. For, by your definition, we, all are witches.” He waved his arm in a sweep to indicate all those gathered around us and smiled, as a father showing pride in his children. “Every one of us. We worship Černobog, the Great Darkness. We worship Veles, Mokoš and Ognebog. And in return, for centuries, we have enjoyed the bounty they deliver. We have prospered from those who have entered these lands like the unknowing victim of the spider wandering blindly into his web.”

“You are witches? Witches all?” My voice came cracked and weak.

“That is what we are. I told you we have never burned a witch here – that is true. Those whom we do burn here are those whose heresy is not to follow the ancient religion of our ancestors. And we guard our religion as zealously as you do yours. We do not burn he who is a witch – we burn he who is not a witch.”

He turned from me and waved his arm in command. At that moment, a procession appeared, led by Vesna, the taverner’s daughter, carrying a flaming torch and naked as she had been in my dreams. Had they been dreams? Behind her four men carried between them on their shoulders a bier, atop of which sat a chair. My horror redoubled at the sight of Father Kryštof, dressed in a white ankle-length chemise and the pointed, conical cap of a penitent. He had been bound to the chair and his screams were stifled by a gag. Our eyes met, his wild with terror, as he was conveyed to the pyre. Pathetic pleading was stifled to whines by the gag in his mouth as he was hoisted, still strapped to the chair, onto the pyre and the chair bound to the stout stake.

A great cheer rose from the crowd as the taverner’s daughter took her burning stave and rammed it into the pyre. Tallow and straw sparked and hissed as the pyre erupted in flame, the terrified priest’s lamenting reaching a new pitch. As the fire surged, the air filled with smoke and the stench of burning flesh, and the night with the screams of the priest, whose gag could not contain his great anguish.

I had fallen into Hell.

I began to sob uncontrollably, overwhelmed by imaginings of the same fate befalling me.

“Do not fret so,” said the baroness, with contempt rather than compassion. “And gather some manliness to yourself.”

“You misunderstand our intent,” said the baron. “We do not seek to burn you. It is our desire that you live among us unharmed. And what has been your trade will remain your trade.”

“I don’t understand, my lord,” I said and gazed at the bright flames, through which the scorched ruin of a man was visible, mobile even now, in death: black twitchings and spasms as his flesh was desiccated by the heat. A dread dance I had, after all, seen often enough before.

“It is simple …” The baron removed his mask. “We merely want to live our lives as we have lived them since the time of Jan of the Black Heart, and times uncountable before him, unfettered and undisturbed by outsiders or those in our number who are infidels to our creed. There was no pretence to your summoning here, no falsity to your commission. Stand up, Judge von Sybenberger, for that is what you will remain: judge and inquisitor.”

I shook my head, bewildered. “But you are all witches …”

“And witches we will remain. There will be examination and inquisition here. There will be trial and torture. And you will preside over it all for as long as you live. That was why I summoned you here. There are those among us who have committed the heresy of Christianity. You will help us find them, and you will condemn them to the stake – and you will test and try those who wander into this place either in innocent ignorance or deliberate intrusion. And all the time you will send your reports back to the Prince-Bishop’s office, assuring them that all the many you have burned were witches.

“You will live well here, and none shall offer you insult or injury, but should you attempt to leave, I promise you we will light the night sky with your burning flesh. Your body and life now belong to us, to the mountain and the castle of the witches. And your soul belongs to Černobog. Resign yourself thereto.”

So that is my story, the story of Witchfinder and Judge Herwyg von Sybenberger. Compelled to preside over countless tribunals, I have commending countless righteous souls to the flame; tortured good Christians until they have slandered and condemned their faith. No different, the baron assures me, to what I did during my time with Judge Boblig. My soul, as was the baron’s intention, has become blackened and spoiled. My corruption is absolute.

But I hide this testimony here, in the dark fabric of this dread place in the hope that one day it will be discovered and the true nature of this place revealed. My entreaty is this: if you have discovered this testimony while dismantling the castle, I beg you to stop. This castle, evil as it is, must stand here for all time and its fabric should never be disturbed; for all the evil that exists within its walls, and that which has leeched from it to poison the lands and people in its shadow, it confines a greater, incalculable evil stopped up beneath it.

And beware, for if you linger in this castle, know that evil will find you, for this is where the Devil hides.

May the Lord have mercy on my soul.

His awareness gathered slowly and remained shrouded in bewilderment for a moment. When Professor Románek came to, he found himself surrounded by workmen, the foreman leaning over him, frowning. Realizing he was lying on the couch in his office, he sat up, only to be rewarded by a wave of nausea and a pounding in his temples.

“Take it easy, professor,” said Procházka.

Románek looked around himself, then over to his desk. “The leather folio … the papers … where are they?”

“What papers?”

“I was reading them, at my desk …”

“You weren’t in here, professor. We brought you into your office after we found you on the floor of the same cell we found Holub. You should have followed your own advice. The fumes – they must’ve gone for you too.”

“But I had them …” protested Románek, “… in my hand.”

Procházka shook his head. “You had nothing. You were only out for a moment. You fell from the ladder.”

Románek frowned, his mind reaching into itself for an explanation. The fumes. It must have been the fumes. “I agree with you, Procházka,” he said eventually. “This place does play tricks with your mind.”

“Well you better rest, after that. You gave us quite a turn. We won’t be using the generators any more anyway – we’ve got the electricity reconnected and we’ll get that cell wall fixed. Then this place will be ready for the arrival of the Devil’s Six. If that really is who’s coming.”

“Yes, that really is who’s coming,” said Románek. “This place has been waiting for them. This is where they belong.”

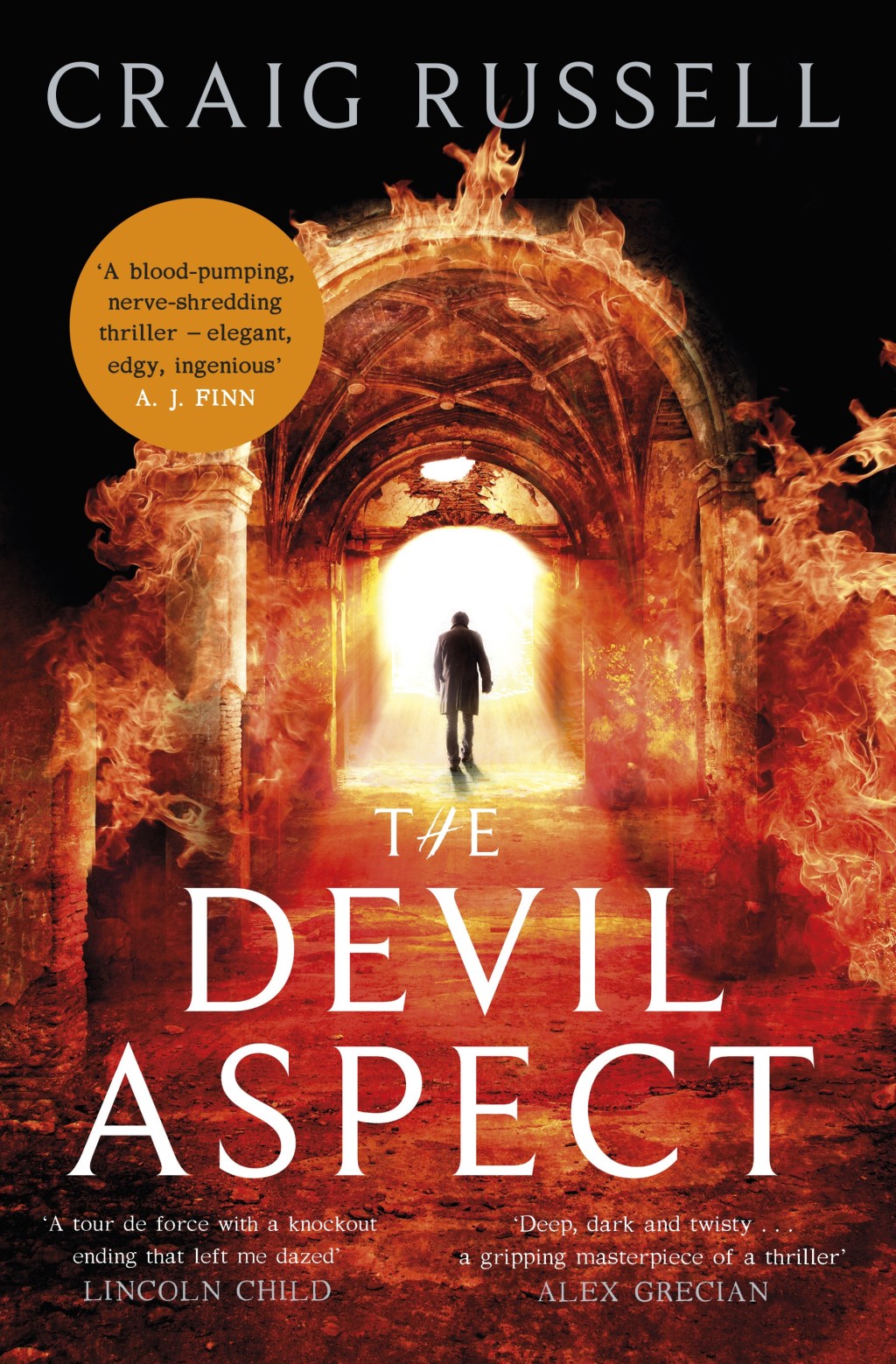

Loved this story and want to read more?

Craig Russel’s novel The Devil Aspect is out in March 2019.

Six confined psychopaths. A killer on the loose.

1935. As Europe prepares itself for a calamitous war, six homicidal lunatics – the so-called ‘Devil’s Six’ – are confined in a remote castle asylum in rural Czechoslovakia. Each patient has their own dark story to tell and Dr Viktor Kosárek, a young psychiatrist using revolutionary techniques, is tasked with unlocking their murderous secrets.

At the same time, a terrifying killer known as ‘Leather Apron’ is butchering victims across Prague. Successfully eluding capture, it would seem his depraved crimes are committed by the Devil himself.

Maybe they are… and what links him with the insane inmates of the Castle of the Eagles?

Only the Devil knows. And it is up to Viktor to find out.