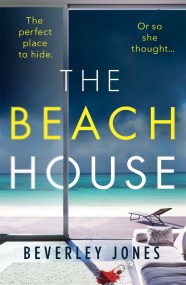

Read an extract from The Beach House

One

Birthday Surprise

The body isn’t the first thing I see when I step into the

kitchen, it’s the length of rope, the knife and the handcuffs.

They’re lying on the hardwood worktop, making the

place look untidy. There’s a metallic tang in the air too, in this room that usually smells only of expensive coffee, a flush of open-window salt air or a $60 rosemary candle. Smell is the organ of memory and memory should be clean and reassuring by design, at least, if I have any control over it.

Nose twitching, I call out, ‘Eli? Are you home?’, stepping forward to put down my grocery bag. Looking at the knife, it’s obviously an ordinary Kitchen Devil, cheap in any hardware store, with no place in this streamlined workspace. New, unused, its gleaming incisored edge looks almost eager to be taken in hand, to enjoy its first bite when, by contrast, the handcuffs are well-used, a lattice of scratches around the keyhole.

The coil of rope is clearly new, gathered to a waist by a length of plush, red ribbon, its velvet splash bright on the back of my eyes as I think, Presents. From someone with strange taste, granted, but who’s still taken the trouble to plan a surprise. Someone who’s snuck inside to leave them just for me. Which explains the unlocked back door when I tried my key just now, brown bag hoisted on my hip, trying not to squash the box of cupcakes – Red Velvet, like the red ribbon – Tilly’s favourite, for her birthday tomorrow.

Tilly! Where is she? comes the hardwired reflex for her safety, but of course she’s not here. My soon to be eightyear- old daughter is at intermediate aikido ass-kicking class in the city with Anoushka, and I’m all alone, in this house, with the gifts. Except I’m not, my head reasons finally, my heart snare-drum jittering to the sudden threat.

It’s been less than thirty seconds since I sailed down Shore Road in my little hybrid, pulled up in the yard and opened the door, but I’m already the familiar fool I swore I’d never be, the woman returning home to find a possible intruder in the house, frowning at the unlocked door, calling out, Anyone home? like a total idiot. I’m the one who freezes in the presence of lurking peril instead of firing her way out of it on her wits, when the suspicion becomes real. Like right now.

Without warning, a ticking fills the afternoon, a countdown reverberating around the winter-light kitchen in segments sharp and clear. As it divides the bursts of my breath, I know I should bolt, but there’s a delay between my brain and my anchored feet. It’s only when the sun slants in through the picture window, filling it with the glowing weight of the afternoon ocean at my back, that I see the figure on the floor.

It’s lying in a classic dead-body pose, invisible crime-scene tape around the one bent leg, one arm out, as if he’s sleeping on his stomach. But no one could nod off with that much blood pooling around their head, so much blacker than the red of the ribbon on the rope, a shiny, jet slick the exact shade the edges of my vision are turning.

My grocery bag escapes disloyally to the floor, leaving me exposed, as I see by my left foot the blunt, metal baton Eli calls ‘the pewter penis’, my name etched on the plaque at its base, smeared with blood.

It’s not my husband lying there, thank God, felled by the ridiculous award he won’t let me stash out of sight in a cupboard. I know this, even though the face is hidden by its uncomfortable angle against the floor. Eli hasn’t popped home early with a bottle of chilled Pinot, his bearlike grin a prelude to Tilly’s rocket-launch into my arms, yelling Mommy, surprise! This man is much slighter and Eli would never be seen dead in stonewashed jeans with frayed hems. He’s wearing Converse trainers too, by no means a dignified outfit to take one’s final dive out of this world into murder-victim stillness.

So, who the hell is he? And what was he intending to do with all that weird stuff on the worktop? The answer arrives like an Amtrak train, exploding the shock that’s held me on the spot, and my feet start pumping towards the door, away from the gifts, from the body, from the knife-edge expectation of a hand on my shoulder.

In all honesty, I’m not that surprised. I’ve waited seventeen years for this moment, for the vice-like grip dragging me back, branding my flesh with four fingers and a thumb.

Not like this though. This is not how I imagined it.

When the inevitable happens, it’s not with a hand clamped on the back of my neck, soft and exposed for the first strike. Instead, as I reach for the door handle, a shadow emerges from the family room. I don’t scream but the noise that comes from my mouth is a guttural cry, forming wordlessly, its meaning clear.

Not now. Not today. I’m not ready.

Then I’m wide-eyed before the face of a Lookout Beach cop, a blanched and hatless kid in the doorway, gripping me by the wrist, his gun drawn in his other hand as I fight for the freedom I’ve always known couldn’t last for ever.

‘It’s OK. Are you OK, ma’am? Are you hurt?’ he demands.

But I can’t answer. I am neither and both, intact, but also not. How can I explain to this uniformed boy that I’m terminally injured, have simply hung on and fought for seventeen years, pushing the sting of sickness back each day, swallowing it down? The fear that I am a bad person and will meet a bad end.

‘Is there anyone else in the house, ma’am?’ the cop shouts now, as his radio crackles, pushing me outside into the sunshine raining on the iron sea.

When I sink onto the grass, another officer is already there and, out along the shoreline, a siren song of emergency responders joins the fret of seagulls, unused to so much vulgar noise and flurry.

‘We’re here, now, ma’am. You’re safe,’ she’s saying, as if insistence can make it so, when the only words I hear in my head are from a season long ago and far away, from a face twisted with rage; a voice that spits, ‘Just remember, whatever I did to her, one day I’ll do to you,’ over and over again

*AN EVENING STANDARD BEST THRILLERS TO READ IN 2022*

'This gripping thriller explores what it's like to have a picture perfect life but with a deep and secret past' EVENING STANDARD

'I devoured it in a single sitting' C. J. COOPER, author of THE BOOK CLUB

'A tense, page-turning thriller' LISA BALLANTYNE, author of ONCE UPON A LIE

___________

When Grace Jensen returns to her home one day, she finds a body in a pool of blood and a menacing gift left for her.

The community of Lookout Beach is shocked by such a brutal intrusion in their close-knit neighbourhood - particularly to a family as successful and well-liked as the Jensens - and a police investigation to find the trespasser begins.

But Grace knows who's after her. She might have changed her name and moved across the world, deciding to hide on the Oregon coast, but she's been waiting seventeen years for what happened in the small Welsh town where she grew up to catch-up with her.

Grace might seem like the model neighbour and mother, but nobody in Lookout Beach - not even her devoted husband Elias - knows the real her. Or how much blood is on her hands.

___________

The hottest, edge-of-your-seat summer thriller, perfect for fans of THE HOLIDAY by T. M. Logan and BIG LITTLE LIES by Liane Moriarty.

WHAT READERS ARE SAYING . . .

'I have devoured this book in one sitting with no regrets. I NEED more'

'A page turner of a book, I couldn't put it down. 5 stars all the way'

'Utterly captivating . . . Compelling, addictive'

'Wow, I loved this one. The perfect setting with a gripping storyline'

'Atmospheric, dark and chilling, I couldn't put it down!'

'A page turner . . . loved everything about this book'

'Definitely one to pack in your bag for holiday'

'An absolutely wonderful and thrilling page turner. It had me on the edge of my seat'